Not one for the traditionalists, Barrie Kosky’s directorial reimagining of Bizet’s classic Carmen pushes the boundaries of what it means to stage a traditional opera within a historical venue in the modern day.

Not one for the traditionalists, Barrie Kosky’s directorial reimagining of Bizet’s classic Carmen pushes the boundaries of what it means to stage a traditional opera within a historical venue in the modern day.

After The Merchant of Venice and Elfriede Jelinek’s Wut, resident director Nicolas Stemann brought Chekhov to the Kammerspiele – The Cherry Orchard premiered in January, 2017. Stemann is not the kind of director who embraces naturalism. In his production of The Merchant of Venice, Shylock never makes an appearance. The director likes to challenge his audience with unusual casting decisions and by changing the text of the play. This time, however, the director leaves the text mostly unchanged and casts every character with one actor.

Courtesy of Thomas Aurin.

Written in 1905, The Cherry Orchard was Anton Chekhov‘s final play. The dying Chekhov was witnessing a time of great upheaval. There were peasant revolts, the social order was being challenged because the ruling class had ignored the need for change for too long. This passivity greatly contributed to the revolution in 1917. Chekhov wrote his drama as a metaphor for the passivity of society in a time of change and its failure to create a future that is acceptable to everyone.

Once upon a time the cherry orchard used to be very profitable. The harvest guaranteed the income of Lyubov Ranyevskaya and her family and secured them a prominent position in society. But over the past years the market for cherries has dwindled and the estate has been losing money. When land owner Ranyevskaya returns to her childhood home to replenish her energy and her finances, she finds herself deep in debt – the estate will have to be auctioned off. Lopakhin, the son of a former serf, offers a solution to save the estate: Cut down the cherry orchard and replace it with holiday homes. To his former masters, this suggestion clearly demonstrates Lopakhin’s lack of culture and is immediately dismissed. The value of the cherry orchard is immaterial. Cutting it down would mean cutting down their place in society, a place that others are also striving to achieve.

Nicolas Stemann focuses on identities, but age and, on one occasion gender, are unimportant. Lyubov Ranyevskaya, who returns from Paris to find solace in her home, is meant to be a middle-aged woman with a teenaged daughter, yet is played by Ilse Ritter (born in 1944) with Daniel Lommartzsch (born in 1977) as her brother Gayev. Firs is played by the youngest actor of the cast, Samouil Stoyanov. Thomas Hauser has taken over for Brigitte Hobmeier as Anya’s governess Charlotte. Stemann’s daring casting choices work quite well in this artificial environment of representation. Samouil Stoyanov adds another, quite threatening dimension to his character Firs because he shares his reactionary views not as a doddery old man but as an energetic firebrand.

The actors do not often interact with each other but speak into microphones as if they were doing a radio play as the director wants to avoid the sentimental atmosphere of more traditional Chekhov productions. Instead, Stemann places his work in the here and now using the characters as contemporary political figures – Ranyevskaya and her family are the passive establishment, the uninspired neo-liberals are represented by Peter Brombacher‘s tired and subdued Lopakhin, the eternal student Trofimov (Hassan Akkouch) stands for the intellectual who knows the truth but is not a man of action, and Firs is a reactionary who longs for the past because everything was so much easier without freedom. His speeches become quite aggressive and threatening as he turns into the spitting image of a fierce AfD (Alternative for Germany) supporter or any representative of the alt right.

Nicolas Stemann has placed Charlotte in the centre of the production. She is not a mere governess, she is a magician, a Romani without a firm identity. After Varya, played by the great but sadly underused Annette Paulmann, states that “only a God can help us now“, Charlotte starts off the second half with her extemporised summary of the first part, which leads to enthusiastic applause. Katrin Nottrodt‘s stage is bare except for a few chairs, microphones, and some electronic equipment and resembles a workshop. Occasionally, the noise of a drill precedes the arrival of logs that are tossed onto the stage. Yet the only prop that features rather prominently is a red velvet curtain that seems rather out of place and moves miraculously whenever Charlotte deems it necessary, only to end up in the dust just like the traditional Chekhov production it might symbolise.

The excellent cast and the intriguing casting choices make this a worthwhile evening although traditionalists might not enjoy Stemann’s bold production. 4/5

Review written by Carolin Kopplin

DER KIRSCHGARTEN will next be shown on 26 March 2018. To find out more about the production, visit here…

The production is in German with English surtitles.

Having read Of Mice and Men for GCSE English and revisiting it last year by choice, I was keen to see the stage adaptation of the modern classic. Many will have experienced the narrative of John Steinbeck’s original novel, but less will have experienced the play on the stage.

“Being out here. Sometimes there isn’t a lonliness like it. So be brave. If you can.”

So speaks Mick, the mentally fading grandfather of an isolated farming family facing cruel circumstances in Simon Longman‘s Gundog at The Royal Court theatre upstairs.

Courtesy of Manuel Harlan.

Bryony Kimmings captures the audience from the moment she walks on stage to kick off her musical masterpiece on cancer. This show is hard-hitting, yet sensitive. It is brutal yet touching. I have never seen anything quite like it.

The concept of the American Dream has been an ideal that has gripped the imaginations, and aspirations of millions, as well as inspired. The old fashioned rags to riches tale consisting of a spacious home, a respectable job and a better quality of living are factors that surely none of us could refuse. Drawing on the incredibly influential Chimamanda Ngozi’s short On Monday of Last Week, writer Saaramaria Kuittinen presents a topical tale of immigration, assimilation and culture.

Courtesy of ASME Productions.

On a miserable foggy weekday morning, stuck in a freezing metro while travelling apathetically to work and reading the latest news on a freshly bought one-pound journal, a yawning commuter notices a glove. Who left it there? Whilst scrolling through websites on the Internet, maybe even when checking this same review, a quiz pops up promising to reveal an individual’s inner tropical fruit – are you a sexy papaya or a cool coconut? Both the solitary glove and the juicy test capture your attention, they distract you. That is what The Department does best. A clandestine organisation that operates discreetly, seeding objects all over the place which bored people will eventually notice and will then water creatively with their minds. The abandoned glove will incite people to build a story, diverging their thoughts from their tedious everyday matters.

Courtesy of the Northern Stage Theatre.

Judas premiered in December 2012, when director Johan Simons was still artistic director of the Münchner Kammerspiele. Simons headed the theatre from 2010 to 2014/15, and several of his own productions were invited to the Berliner Theatertreffen – Sarah Kane’s Gesäubert/Gier/Psychose 4:48 (Cleansed/Greed/Psychosis 4:48, TT 2012) as well as Elfriede Jelinek’s Die Straße. Die Stadt. Der Überfall (The Street. The City. The Holdup, TT 2013). In 2013, on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of the Münchner Kammerspiele, the magazine “Theater heute” granted the “Theater of the Year” award to the theatre.

Courtesy of Judith Buss.

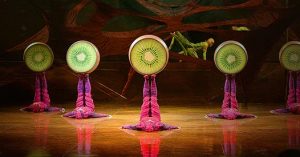

The beauty of planet Earth lies within its complexity. Multiple factors co-dependently fuelling our day to day. Our knowledge of the animal kingdom expands, but will always remain mysterious to humanity, but this is where the magic lies. Cirque du Soleil’s OVO taps into our fascination with the animal kingdom, returning with their latest show at the Royal Albert Hall.

Courtesy of Cirque du Soleil.

It seems that, despite the ongoing criticism, the Münchner Kammerspiele are doing something right. Two of their recent productions are invited to the 55th Berliner Theatertreffen – Trommeln in der Nacht by Bertolt Brecht, directed by Christopher Rüping, and Mittelreich with an all-black cast, based on the novel by Josef Bierbichler and the production by Anna-Sophie Mahler, directed by Anta Helena Recke. Only ten outstanding productions from theatres all over Germany are chosen every year. (Reviews of both productions can be found on this website.)

Courtesy of Thomas Aurin.